This is the fourth installment of my “SEO 201” series, following:

- “Part 1: Technical Rules”;

- “Part 2: Crawling and Indexing Barriers”;

- “Part 3: Enabling Search-engine Spiders.”

No matter which aspect of search engine optimization you’re engaged in — from content optimization to increasing link authority — architecture drives SEO.

For the purposes of this article, “architecture” describes what content is represented and how it’s organized. A site’s architecture is typically expressed in sitemap and wireframe forms. The architecture decisions made during the site’s creation impact SEO performance, at a point in the site’s design and development when teams rarely think about bringing SEO into the picture.

For example, an ecommerce site that specializes in clothing may want to rank for a variety of age, gender, and product type phrases like “men’s clothing,” “girls’ shirts,” and “jeans.”

To do so, the pages most suited to rank for those phrases will need to send strong relevance and authority signals to the search engines. Any number of architecture decisions could hinder the site’s ability to rank.

Content Optimization and Site Architecture

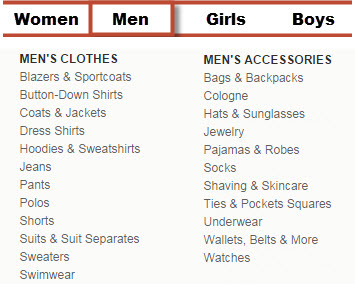

To optimize a page for SEO, you need to have a page to optimize. The architecture determines which pages do and do not exist. For example, if the site’s architecture segments customers into audience and gender before clothing type, there won’t be a genderless clothing type page to optimize, as in the example below.

If the site’s architecture segments customers into audience and gender before clothing type, there won’t be a genderless clothing type page to optimize, as in this example.

This site doesn’t have a page suitable for optimization for “jeans,” because the only jeans pages that exist are for women’s jeans, men’s jeans, girls’ jeans, and boys’ jeans. Because the site forces customers to choose between clothing for women, men, girls or boys before it allows choice of product type, the genderless product type page does not exist. If ranking for the most general product type keywords is important to this company, its SEO would recommend altering the architecture to integrate pages and navigation for genderless product types.

Even when pages exist, ecommerce sites are notorious for being stingy with textual content. The templates for category pages in particular tend not to contain space for descriptive text and headers. This is due to architecture work on wireframes without SEO input.

Ironically, category pages are the best chance an ecommerce site has to rank for valuable product type phrases like “men’s clothing” and “girls’ shirts.” Individual product detail pages rarely have the authority or keyword relevance to rank for product type keyword phrases. Category pages, on the other hand, are born to rank for those phrases. All they need is a couple of sentences of body copy and an H1 heading, as well as an optimized title tag and meta description, declaring their raison d’etre — their reason for existence.

Lastly, architecture is responsible for the words used in the navigation, which in turn has an impact on SEO performance when the navigation is textual rather than image-based. The navigational anchor text passes a keyword relevance signal to the page being linked to. When a site uses valuable keywords in the navigation, it boosts the keyword relevance of those pages. This can certainly be overdone, so do it only where it’s most valuable and natural. Close interaction between the site architect and the SEO professional is the only way to achieve this balance.

Authority and Site Architecture

The home page of the site tends to be the strongest because typically more links from other sites link to the home page than any other page of the site. Spreading that link authority from the home page, and from other pages that naturally acquire more authority, throughout the site helps more pages rank more strongly.

The home page of the site tends to be the strongest because typically more links from other sites link to the home page than any other page of the site.

Navigational links are the best way to accomplish this goal. The pages linked to in the navigation receive an authority boost from every page on the site because search engines treat links like little votes of the value of a page. More links to a page means that page has higher value, in general.

Site architecture determines which pages are linked to on which pages. When architecture and SEO work together, they can meet the twin goals of helping customers find the right pages while they’re on the site and helping customers find the right pages via organic search.

For example, in a redesign the architecture may call for a simplified navigational structure that customers can read in a single glance with fewer choices and rollovers in the header navigation. The SEO professional may advise against this course, or lobby to leave a few of the more valuable pages in the navigation that had been cut. Removing navigational links would have a negative impact on SEO performance for the pages removed, but keeping the most valuable pages in the navigation could minimize the risk while still achieving the goal.

Where navigational elements are used also impacts SEO performance. If the header or sidebar navigation changes based on the section of the site you’re in, the pages linked to will not draw link authority votes from every page on the site, only from the pages on the site that feature that version of the navigation.

For extremely large ecommerce sites consistent sidebar navigation may not be an option. The clothing site mentioned earlier, for example, probably has tens of thousands of SKUs in thousands of subcategories. Attempting to cram all of those navigational options into a single sidebar navigation would be require so much reading and scrolling that the site would unusable. Sites with smaller offerings, however, should endeavor to keep their navigational elements consistent across the entire product catalog.

Technology and Site Architecture

All of the great usability features planned for in the architecture phase can lead to some challenging SEO issues as well. How navigational elements are coded can render them uncrawlable to search engines. If pages can’t be crawled, they also can’t be ranked or drive organic search traffic and sales to a site. I addressed his in “SEO 201, Part 3: Enabling Search-engine Crawlers.”

Outside of navigational links, a site’s architecture may call for other forms of access that act as roadblocks to search engines. Search engines spiders traditionally crawl links between pages and index content on the pages. Entry boxes that require some input before proceeding to the next page break that paradigm. Password prompts, internal search boxes and lead generation forms are all blockers to SEO performance.

A site that depends solely on a user-generated response in an open field for access to lower level pages in the architecture will typically have SEO issues. This issue is largely theoretical for ecommerce sites because so few of them place their product catalogs behind passwords and lead generation forms.

Companies that require memberships to purchase, however, may be tempted to place most of their content behind a password to induce registration. This goal needs to be weighed against the desire to drive new customers via organic search, however, which can only be done by making some content that can be relevant and authoritative for valuable keywords outside publicly available.

For the next installment of our “SEO 201″ series, see “Part 5: Evaluating Ecommerce Platforms.”